My first encounter with Alberto Di Fabio is at a house warming party in a beautiful apartment overlooking the ancient chariot-racing venue of Circo Massimo. People are talking, lounging on couches, and sipping wine. I look over and see that two people have decided to turn the living room into a dance floor. One of them is Alberto. I am fascinated with his guileless demeanor and the huge grin on his face as he dances as if no one is watching.

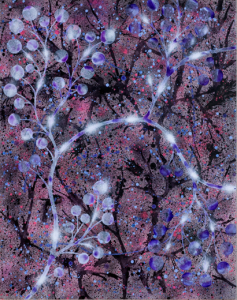

A few days later I encounter Alberto’s big smile again when he greets me at the door to his Pigneto studio. He ushers me inside and I am immediately impressed by the large, colorful, and intricate abstract works that adorn the walls, lean propped against furniture, and are spread out on the floor. Works in progress sit on tables next to paints and various implements. “Welcome to the spaceship,” he says with a grin, and in a no-nonsense approach that I greatly admire, Alberto skips right over any small talk or formality and immediately digs deep. As his voice echoes under the vaulted ceiling of the expansive workspace, I get the sense that I’m only hearing one side of Alberto’s phone conversation with the Cosmos. “We just need to breathe and say thank you that we are healthy and that we are here.” He continues in a pensive tone, “If you are with one woman, you want to be with one hundred women. If you are at a cocktail party, you’re missing other cocktail parties. The person who lives in London dreams of living in New York.”

“We just need to breathe and say, thank you that we are healthy and that we are here.”

I ask Alberto about his cosmology. “I was born Catholic in a small village in Italy but I learned a lot about other religions when I was in New York.” He tells me he now appreciates all religions and that he doesn’t necessarily pray to anyone in particular. “I believe in Dio quantico…a quantum God. I try every morning to give thanks for what I have. It’s very important to believe in what you did and try to make it a little better.” For Alberto, prayer is a ritual used for various purposes. He’ll pray to re-center himself in the middle of a long day, stopping to express gratitude for all the positive things in his life. He’ll pray when he starts a new painting. “The white canvas is horrible, terrible, so I pray for help and also give thanks because I can’t do it by myself.” Impressed by Alberto’s diligence in developing the more subtle aspects of his character and perception, I ask him if he has ever spent time in a sensory deprivation tank. He tells me he tried it once in New York but it made him claustrophobic. He adds he doesn’t feel the need for the tank: “I try to live every day in that state.”

Since his work blends the human experience with the cosmic, I ask Alberto about his opinions of the Mars mission that is being speculated on by various global interests. “If you go 24 kilometers up it is empty cold loneliness. We are a small flower. But maybe we are Martians. Maybe years ago we were there, we destroyed everything and then we came here!” We both laugh.

With more than 250 art shows under his belt at age 50, that’s an average of five shows per year if he started at birth. I ask Alberto if he would consider himself a prolific artist. He responds, “Yes. A little bit too much. I’m obsessed. I spend all my time in the studio, 12 hours a day.” Alberto has been married 18 years to his wife Yumiko. They have three children. I ask him how he balances work and home life. His answer is passionate. “Artists … we are so egocentric. We need attention. We are always not so happy for the show, for the things… it’s so boring in the end! I’ve seen so many friends get divorced. So I have tried for a long time to cut my egocentrism.” He tells me his solution is to give, to be generous with his wife and children. He also finds that caring for plants helps. “If you don’t water the beautiful rose it will die. The same is true at home. The family is its own small world.”

Alberto’s work has a fractal quality to it. His designs reflect the patterns of things as large as galaxies and as small as synaptic clusters or atomic structures. In 2014, he was invited to show his art at CERN Laboratories in Geneva, Switzerland. I ask Alberto to tell me more about the circumstances behind this opportunity. He say that one of his paintings caught the attention of people in the science community because it looked very similar to a photo of a galaxy captured for the first time by the Hubble telescope in 2010. The interesting thing is that the painting is in Alberto’s 2008 catalog. “My theory, in the last few years of painting, is that the electromagnetism we have inside us can go out there and then come back. Our wave. It’s a question of training. It’s a question, really, of praying.

Alberto’s work has a fractal quality to it. His designs reflect the patterns of things as large as galaxies and as small as synaptic clusters or atomic structures. In 2014, he was invited to show his art at CERN Laboratories in Geneva, Switzerland. I ask Alberto to tell me more about the circumstances behind this opportunity. He say that one of his paintings caught the attention of people in the science community because it looked very similar to a photo of a galaxy captured for the first time by the Hubble telescope in 2010. The interesting thing is that the painting is in Alberto’s 2008 catalog. “My theory, in the last few years of painting, is that the electromagnetism we have inside us can go out there and then come back. Our wave. It’s a question of training. It’s a question, really, of praying.

“There was a time in my younger life when I had the perception of this Matrix, you know, like the movie.” He tells me about a period when he nearly had a mental breakdown. “You get scared when you see the code, the real code, but I never talk about that. I try to just describe it in more poetic terms.” I’m fascinated with the idea that the search for transcendent knowledge can be a dangerous path. One of the most well known casualties of this pursuit is the philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche. I am reminded of the passage he penned a couple years before he was admitted to an asylum and diagnosed as clinically insane: “And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” I ask Alberto what he thinks about this. He replies, “One life is not enough time to train to encounter that level of reality.” His voice softens. “I’m closer to the material world. I enjoy living, eating, sleeping, whatever, so that other dimension can be really scary. But all my work does come from there.”

“There was a time in my younger life when I had the perception of this Matrix, you know, like the movie.” He tells me about a period when he nearly had a mental breakdown. “You get scared when you see the code, the real code, but I never talk about that. I try to just describe it in more poetic terms.” I’m fascinated with the idea that the search for transcendent knowledge can be a dangerous path. One of the most well known casualties of this pursuit is the philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche. I am reminded of the passage he penned a couple years before he was admitted to an asylum and diagnosed as clinically insane: “And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.” I ask Alberto what he thinks about this. He replies, “One life is not enough time to train to encounter that level of reality.” His voice softens. “I’m closer to the material world. I enjoy living, eating, sleeping, whatever, so that other dimension can be really scary. But all my work does come from there.”

A few days later Alberto invites me into his home where I have the pleasure of encountering his whole family all together. Their living space is absolutely stunning. Yumiko is intelligent, passionate and a lot of fun to be around. Their three beautiful children are like angels. And all of a sudden it makes sense. There are two truths, the objective and the subjective. Subjective truth can be found in love, relationships, and the enigma of human life. Objective truth is like Everest. Its peak is clearly defined, a still point in a chaotic and confusing universe. It’s hard to get there, but you know the moment you arrive and plant your flag. I see the appeal. But some of the most accomplished mountain climbers lose their lives while others with considerably less skill survive. It comes down to an understanding of one’s own limits. This capacity is what allows Alberto to journey up that mountain and know when to turn around and head home so others can benefit from what he brings back. Those who go too far may witness amazing things, but those experiences are lost forever, unable to be shared with the rest of us. For Alberto, his family is its own summit, at least as important; and that is what keeps him coming back.